A Chance for Fire Research and Recovery at a NEON Desert Site

January 24, 2025

Across the U.S., many ecosystems are vulnerable to wildfire. The wild areas where the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON) collects data are no different.

In August 2024, the Sand Stone Fire northeast of Phoenix, AZ burned through the NEON aquatic field site at Sycamore Creek (SYCA). Located on the edge of the Tonto National Forest, this site is part of the fragile Sonoran Desert ecosystem, where fire poses a threat that can drastically alter the landscape and habitat. Because NEON collects highly standardized data from 81 field sites on a regular basis, data collected from before and after the Sand Stone Fire at SYCA could provide a chance for researchers to delve into the effects of wildfire on this unique ecosystem.

At the NEON SYCA site, the Sand Stone Fire in 2024 burned saguaro cacti and mesquite trees, and damaged NEON infrastructure cables.

The Sand Stone Fire at NEON Sycamore Creek

The Sand Stone Fire, ignited by lightning on July 25, 2024, burned approximately 27,390 acres in the Tonto National Forest, managed by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS). Fueled by large volumes of dry grass and brush, the fire burned for more than three weeks and was not fully contained until late August. In the aftermath of the fire, blackened saguaro cacti and mesquite can be seen at SYCA and across the surrounding areas. Despite the damage to the field site, the infrastructure at SYCA provides an important opportunity to document wildfire impact and recovery at a working NEON field site. Over the years, NEON has documented a variety of disturbances at NEON field sites—including floods, hurricanes, and nine other wildfires—using airborne remote sensing surveys and other methods. The data gathered by the NEON program provide an invaluable view into the aftereffects of these events. Read more: Monitoring Disaster Recovery from the Air with NEON.

“It was devastating to see this piece of beautiful desert burn, and the site and its vegetation will never be quite the same,” says Ingrid Holstrom, senior field technician in NEON’s Domain 14, the Desert Southwest. “However, incidents like this really underscore the importance of long-term observational data collection. We are capturing changes in the ecosystem and the effects of change in real time. These data could be really valuable to the field of desert fire ecology.”

How are fires changing the Sonoran Desert?

Sycamore Creek is an intermittent desert stream running through the slopes of the Mazatzal Mountains in the Tonto National Forest – the largest forest in the state, covering over 2.9 million acres. The area around Sycamore Creek is a quintessential Sonoran Desert landscape, featuring iconic plant species like saguaro cacti (Carnegiea gigantea), prickly pear (Opuntia spp.), and velvet mesquite (Prosopis velutina), along with desert wildlife such as mountain lions, javelinas, and roadrunners. At the SYCA field site, riparian tree species such as Fremont's cottonwood (Populus fremontii), Goodding's willow (Salix gooddingii), and Arizona sycamore (Platanus wrightii) line the banks of the creek.

This landscape is undergoing rapid ecological change. Much of the Sonoran Desert has already shifted or is shifting to novel grassland. In an already fairly unstable system, humans have added some significant changes, starting in the early 20th century when people introduced red brome grass (Bromus rubens) from Europe as forage for livestock. Over the last 100 years, red brome and other invasive grasses like buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare) have spread aggressively across arid regions in the Southwest, altering the natural balance of these delicate ecosystems and reshaping the landscape in profound ways.

One of those ways is an increased risk of intense fire. Unlike the sparse, relatively more fire-resistant native vegetation of the Sonoran Desert, invasive grasses can grow densely and dry out quickly, creating a continuous fuel bed that allows fires to spread rapidly and burn at higher intensities. These fires can devastate native plants such as saguaros and palo verde trees. They create a destructive cycle: invasive grasses fuel the fires, fires clear the landscape for more grasses to grow, and native species are increasingly pushed out.

Over the last five years, about 20% of the Sonoran Desert area managed by the Tonto National Forest has burned at least once. Over the last 50 years, 40% has burned at least once, and some areas have burned three or four times. While most native desert shrubs are adapted to some fire, and can sprout back fairly quickly after a few years, they are not adapted to more frequent or intense fires. It can be likened to how a Ponderosa pine forest needs fire all the time, but at lower intensity and is not adapted to infrequent, high-intensity fire.

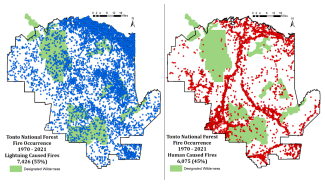

These high intensity fires, which are becoming more common in the Sonoran Desert, will irreparably damage the shrub ecosystem. The shrubs will eventually be overcome by the damage and the system will transition to grassland, especially near highways or in areas with intense human recreation where fires are more frequent (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Tonto National Forest fire occurrence caused by lightning (left) vs. human activity (right). The lines of fires caused by humans are more clustered and occur along high-activity areas like roads. Credit: Dr. Mary Lata, USFS.

Use NEON to Study and Predict Fire

Researchers studying the effects of wildfire on desert ecosystems can leverage NEON for comprehensive, open, standardized monitoring data on key ecological variables such as vegetation structure, soil composition, atmospheric conditions, and hydrology. These datasets can enable scientists to analyze pre- and post-fire conditions, track ecosystem recovery over time, and develop predictive models for future fire events in desert landscapes. Moreover, NEON remote sensing data, including high-resolution lidar and hyperspectral imagery, can provide valuable insights into changes in vegetation cover and topography following wildfire events.

“At SYCA, the surface water in Sycamore Creek was already starting to dry up prior to the Sand Stone Fire, not uncommon for that time of year,” says Abe Karam, Domain Manager of Domain 14. “However, we were able to collect a few sets of surface water chemistry samples from some of the shallow, isolated pools that remained in the creek the after the fire, as part of NEON’s routinely scheduled water collections at the site. Once surface water returns to SYCA – it's still dry as of January due to the La Nina winter we are experiencing – I'm hopeful our post-fire stream data will be valuable to the science community.”

In addition to its extensive data resources, NEON offers various Research Support Services (NRSS) that can enhance wildfire studies in desert ecosystems. These services provide cost-recoverable access to NEON infrastructure, deployable sensors, field observations, and expert consultation to tailor data collection to specific wildfire-related research needs. For example, deploying additional soil moisture sensors or requesting extra vegetation sampling in burned areas can help scientists better understand post-fire flora changes and soil chemistry impacts. This support also extends to collaboration opportunities and logistical assistance that can facilitate many kinds of wildfire studies.

“The Sand Stone Fire is not the only recent fire to impact the Sycamore Creek watershed,” says Karam. “The long-term nature of NEON documenting change at the site will be important for addressing pertinent questions. There's a unique opportunity for researchers to explore post-fire watershed impacts by leveraging NEON data and utilizing the NRSS program.”

View highlighted past and current Research Support Service projects here.

Looking Ahead: Adapting to the New Fire Regime

The Sand Stone Fire and similar events are stark reminders of the ecological challenges that the Sonoran Desert faces. Invasive grasses have fundamentally altered the region, making it more fire-prone and less resilient to recovery. For land managers, adapting to this new fire regime requires a combination of research, proactive management, and community engagement. At Tonto National Forest, adaptation includes planning prescribed burns in the spring to clear out excessive biomass that could fuel large fires later in the season.

While these measures can help, it is likely that the Sonoran Desert will be permanently changed by non-native grasses and the fires that follow. Decades of incursion by the grasses, along with impacts from fires, livestock, flooding and human activity, are slowly changing the soil composition in the region, making it less suitable for native species of cacti and mesquite. The ecosystem will not be able to shift back to what it once was for numerous decades, if ever.

NEON's extensive data collection at Sycamore Creek and other field sites will be critical in helping researchers and land managers understand these profound ecological changes. By providing long-term monitoring of vegetation, soil, hydrology, and climate, NEON offers invaluable insights into how fire and invasive species are reshaping desert ecosystems.