Getting to Know the NEON Domains: Prairie Peninsula

February 24, 2021

View the Prairie Peninsula Domain storymap here!

This blog series explores each of the 20 NEON ecoclimate Domains and the field sites within them.

In the middle of North America, the eastern forests give way to the tallgrass prairie. This is the Prairie Peninsula (D06), in the heartland of the U.S. Sometimes called "America's Breadbasket," this region provides ample opportunity to study the impact of agriculture and land management practices on tallgrass prairie ecosystems. It also provides a unique view of a transitional zone between the prairies and the eastern deciduous forest.

Defining the Prairie Peninsula Domain

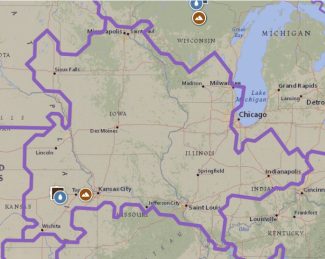

D06 covers 575,000 km2 (222,000 square miles) of the American Midwest, including most of Iowa and Illinois and parts of Indiana, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Missouri, and eastern Kansas and Nebraska. All five NEON field sites are located in eastern Kansas.

Map of Domain 06 - Prairie Peninsula

Most of the Domain is characterized by tallgrass prairies, which feature a mix of native grasses adapted to the rocky soil and fierce winds. More than 600 native plant species are found in the eastern prairies, dominated by big and little bluestem, Indiangrass, and switchgrass. Woody shrubs, including sumac and buckbrush, are also found throughout the prairies. The prairie ecosystems depend on periodic fires to clear out woody growth and allow native grasses to thrive. At the eastern edge of the Domain, the prairie meets the eastern deciduous forest, which features a mix of oak, ash, hackberry, and other hardwoods.

In addition to fire, the prairies were shaped by large grazing ruminants. Historically, bison roamed across the grasslands, and they can still be found in protected areas today. Now, white-tailed deer and cattle are the most common grazers. Other wildlife throughout the region includes coyote, raccoon, opossum, striped skunk, and the threatened eastern spotted skunk. The prairie also supports a diverse range of birds, including the Greater Prairie Chicken, which has breeding grounds at the Konza Prairie field site.

The climate features warm, wet summers and cold, dry winters. Spectacular storms can arise in the summer when moist air from the Gulf of Mexico collides with cooler, drier air from the north. Tornados periodically tear through the flat prairie lands. Winter temperatures can drop well below 0°C (32°F), and summer highs can top 32°C (90°F).

The flat prairie landscape and climate have made the region especially attractive for agricultural activities, including growing crops (mainly corn, wheat, and soybeans) and cattle ranching. Human activities have had a profound impact on the land, pushing out native tallgrass species across most of the region.

Domain 06 has five field sites, three terrestrial and two aquatic:

- Konza Prairie Biological Station (KONZ) – Terrestrial

- Konza Prairie Biological Station (KONA) –Terrestrial

- Kings Creek (KING) – Aquatic

- University of Kansas Field Station (UKFS) – Terrestrial

- McDiffett Creek (MCDI) – Aquatic

Konza Prairie Biological Station and Kings Creek

The Konza Prairie Biological Station (KPBS), hosted by The Nature Conservancy and Kansas State University, has a history of ecological research dating back to 1971. It has been a Long-Term Ecological Research Site (LTER) site since 1980. Research programs through KSU and LTER focus on the impact of agriculture (especially grazing), fire, and climate change on tallgrass prairie ecosystems.

Prescribed burn at KONZ tower in 2020

The station is located in the Flint Hills region of northeastern Kansas, which contains the largest remaining area of unplowed tallgrass prairie in North America. The two terrestrial sites here, KONZ and KONA, provide a contrast between pristine native prairie and cultivated land in eastern Kansas. KONZ is maintained as a natural prairie ecosystem with minimal management, including controlled burns. KONA, 5 km (3 miles) to the west, sits on land that has been used for agriculture and grazing since the early 1900s. It is now maintained by KSU as an agricultural research station. The KONA plots are located in agricultural fields supporting a mix of corn, soybeans, wheat, oats, and sorghum.

Kings Creek in September 2020

Kings Creek (KING) is colocated with the KONA field site. It is a second-order stream draining a watershed of mixed agricultural, pasture, and prairie land. At the sampling location, it is shaded by a mature deciduous gallery forest with oak, elm, hackberry, hickory, and walnut. The creek hosts 23 known species of fish.

University of Kansas Field Station

UKFS tower trail

UKFS is just north of Lawrence, Kansas, on the eastern border of the state and about 130 km (80 miles) east of the Konza Prairie sites. This far east, the land transitions to eastern deciduous forest. The field station is in a transition zone between forest and tallgrass prairie, with most of the sampling plots located in forested areas dominated by white ash and hackberry.

The field station was established in 1947 to advance natural resource stewardship. The area was logged and farmed from the mid-1800s through the early 1900s. Since the establishment of the field station, KU has maintained the land for research, conservation, and recreation. The land is lightly managed with controlled burns and other conservation approaches to maintain native ecosystems. The Kansas Biological Survey manages the field station and conducts research focused on air and water quality and ecosystem health.

McDiffett Creek

McDiffett Creek (MCDI) frozen in winter.

McDiffett Creek (MCDI) is located in the Flint Hills region about 25 km (15 miles) southeast of the Konza Prairie sites. It is a second-order stream flowing through agricultural land, providing a contrast to the more pristine Kings Creek.

The MCDI sampling reach is encompassed within the Urban Prairie Research Area, managed by the Konza Biological Station with KSU. The surrounding landscape consists of a mix of native prairie, historically cultivated lands, and land currently used for grazing or hay. Agricultural fields upstream are rotated with corn, wheat, and soybeans.

Exploring Land Management and Climate Change in the Eastern Prairie

Data gathered at the NEON field sites will help to answer important questions about the impact of agriculture and other land management practices on prairie and transitional ecosystems in the Midwest. The field sites were chosen to provide a contrast between more pristine native habitats and lands used for active grazing or crop growing. The Konza Prairie Biological Station and University of Kansas Field Station both implement a variety of land management practices; NEON data will help researchers understand how land use and management decisions—including controlled burning and grazing—impact the health and resilience of these ecosystems.

Grasshopper at KONZ

Aside from land management, the D06 field sites provide a window into the effects of climate change and invasive species in the eastern prairies. Average temperatures in Kansas have already risen at least 0.5°F over the last century and are expected to continue to warm over the next several decades. Warmer temperatures lead to greater evaporation and drier soil in the grasslands. At the same time, the timing and volume of precipitation have changed, with a greater likelihood of intense rainstorms and flooding. These changes are expected to have a profound effect on both native habitats and agricultural yields in the coming years.

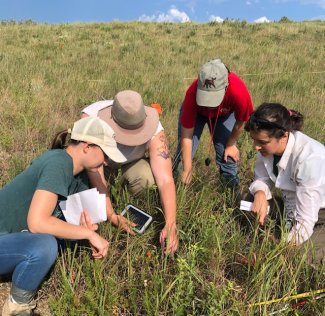

KONZ plant diversity protocol

Invasive grass species are changing the composition of native tallgrass prairies, and invasive woody shrubs threaten to take over grasslands in the transitional zones. Forested areas in the east are threatened by both invasive plants – such as Japanese honeysuckle and Bradford pear – and tree-damaging insects such as the emerald ash borer and the Asian longhorn beetle. These destructive species target hardwoods in the deciduous forests. The NEON program will help researchers monitor the spread of invasive plant and insect species in the Prairie Peninsula.

Wildflowers at KONZ

Another insect mystery – this one involving ticks – has also been uncovered through NEON sampling. Ticks are found in abundance at the more pristine KONZ and UKFS field sites (samples are archived through the NEON Biorepository and the U.S. National Tick Collection). Yet, at the agricultural plots at KONA, no ticks were found in 2018 or 2019. Data from the NEON program could help researchers studying tick populations to understand why this discrepancy exists.

Over the last 100 years, most of the tallgrass prairies have been lost to human settlement, croplands, and grazing. Effective land management practices are urgently needed to preserve the native prairie ecosystems that remain. Data from our Kansas field sites will help to answer important questions around prairie conservation.