Life in the Pits

June 10, 2013

by Derek Smith and Josh Roberti

Two Associate Scientists at NEON reflect upon finding themselves in a seven foot deep hole.

Josh: As a meteorology student, I never thought too much about soil; my mind was focused on the atmosphere. Fast forward a few years and I’m continually finding myself seven feet below ground, surrounded by soil in a gravedigger’s masterpiece. But don’t worry, I’m alive, standing, and ready for action. I have a rock hammer, pick axe, gardening knife, shovel, crowbar, hardhat, gloves, safety glasses, and even a blinding orange vest.

Derek: I used to love digging when I was a kid, whether it was in the sand at the beach or in the dirt in my parent’s yard (to their dismay). Now at 25 I feel I’ve gone full circle and I again find myself digging in the dirt, except now I call it soil and get paid to do it. I guess you never really know where life might take you. So why do we keep finding ourselves digging? One reason – in the name of Science! More specifically, we are taking soil samples to understand soil properties specific to the regions represented by our sites. The information we gather from these samples and from the holes we dig will help us calibrate soil sensors and place them at appropriate depths. We'll also capture a snapshot of soil properties at the site that will inform the development of future NEON data products. Ultimately, these data will provide insight into many interactions and influences among the Earth’s biosphere, hydrosphere and atmosphere. Ed Ayers, a Soil Ecologist at NEON, heads these “Soil Pit” endeavors. Ed and other members of NEON’s Science Team (such as Derek and I) are constantly traveling throughout the United States gathering soil samples. So far our soil pit excursions have landed us in Alabama, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Massachusetts, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Virginia. Over the course of the next few years we will sample soils from all of NEON’s terrestrial sites.

Life in the Pits: The Sampling Process

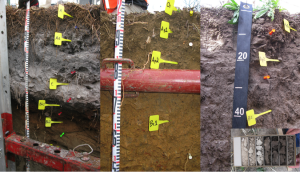

Once the metal frame completely surrounds the soil, we wedge rubber mallets between the metal frame and the surrounding soil wall and hammer a carpenter’s square into the soil directly below the frame. This loosens the soil below the sample so we can insert the bottom plate. Next, we brace ourselves and hoist the sample out of the pit. Each boxed sample can weigh more than 100 pounds (our heaviest sample to date weighed 173 lbs), and because of the placement of the trench box beams, this part of the process often results in poor posture and awkward lifting. Once it’s out of the pit, we place the top plate onto the metal frame, strap together the full box of soil with metal bands, and place it all into a lined and padded Pelican case. We then dig down to the next horizon, which can take upwards of three hours, and start the entire process all over again. At each site we usually gather six of these soil blocks. We take three other soil samples from each horizon. One of these samples is for biogeochemical analyses and includes pH, texture, elemental analyses (including carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and iron) and conductivity. In the event that you feel compelled to explore the nitty-gritty details of soil classification and laboratory methods, NRCS is a great resource for technical information. We then collect a second sample for NEON’s soil archive – a collection of soil samples from all across the United States. Internal and external scientists will be able to request these samples in the future for research needs. Finally, we take a bulk density sample with a soil corer. We send the soil blocks as well as biogeochemical and bulk density samples to external laboratories for analysis. While all this is going on, our counterparts on the terrestrial ecology team are working beside us to measure underground biomass – more on that in a future post. With sixty terrestrial sites to build and sample at across the US, soil pits seem to be a normal part of life for us now and in the foreseeable future. Josh has recently returned from a somewhat messy soil pit in Alabama (below), while at the moment I (Derek) am at ~30,000 ft in transit to the next soil pit at the Smithsonian Conservation Biological Institute in Front Royal, VA. I hear the cicadas have just emerged from their 17-year cycle, which should add yet another layer of complexity to the task. We’ll keep you posted if we’re ever able to get Mike Rowe from Dirty Jobs to join us at one of our pits.