Spotlight

Women in Ecology – Ceara Talbot

January 8, 2025

Unique perspectives and career paths are a theme among the women scientists we have interviewed over the years. Their voices are crucial, bringing experiences that help spark creativity and innovation to push research forward and make sure scientific discoveries benefit a broader range of people across backgrounds and disciplines.

For our latest Women in Ecology interview, we spoke with Dr. Ceara Talbot, a postdoctoral fellow at Carnegie Science. Once interested in the veterinary sciences, she enrolled in a college elective that changed her trajectory. Here, Talbot shares her career journey, what keeps her motivated in the field, how NEON can drive important research, and the challenges of being an ecologist.

Can you tell us about your current role and what inspired you to become involved in your research?

In college, I started doing my bachelor's degree in biology with the intention of going to veterinary school. In my second year, the only elective that fit my schedule was conservation biology. While I was reluctant to take it, it ended up changing my entire career trajectory. The class went on a lot of field trips to different places where we focused on conservation efforts. We went to a river that had recently experienced an extreme flood. As a result of the flood, the entire section of the river started to flow backwards. We were standing in an empty riverbed that was once filled with water. After this extreme event, it was empty and had displaced many organisms. I remember standing in that empty riverbed and thinking about how this happened so quickly, completely changing the landscape.

This experience sparked a lot of questions for me about the importance of the landscape and how easily it can be altered, and it made me a lot more interested in the environment and ecology. To learn more, I accepted internship opportunities that included many different types of research. I worked with rare plants and threatened freshwater mussel species, and also conducted population surveys in forests and in rivers. When it was time to go to graduate school, I cast a wide net and applied to all sorts of programs that had nothing in common. The only thing I knew was that I really liked research and that I had broad interests.

Talbot deploying a plankton net to sample zooplankton at Arrowhead Lake, CA. Photo credit: Braden DeMattei.

I ended up doing my master’s degree in freshwater ecology. I worked with Dr. Maggie Xenopoulos at Trent University in Canada; her work intrigued me because while most aquatic ecologists or freshwater ecologists only focused on a singular type of water body – like a river, stream, or lake – she focused on all three. From her, I realized that I didn’t have to make as narrow as a decision about my Ph.D. as I originally thought.

I started my Ph.D. in Dr. Stuart Jones’s freshwater ecology lab at the University of Notre Dame. There, I read a lot, and I realized how important the surrounding landscape is to aquatic ecosystems, yet that it’s difficult for aquatic ecologists to incorporate detailed information about those systems in their own work. From there, I decided to focus on both systems and their connections. I still work in a freshwater ecology lab, but it does not necessarily define what I do. What I do now involves linking carbon and water cycle observations across ecosystems, with mechanistic models. They tend to target a specific carbon flux, which is the flux of carbon from terrestrial to aquatic ecosystems, like from forests to rivers, streams, or lakes.

Talbot in the field at the University of Notre Dame Environmental Research Center. Photo credit: Randi Notte.

What keeps you motivated in your ongoing studies and dedication to this field?

From a scientific perspective, we have more data now than we have ever had, and computing resources are becoming increasingly available to ecologists. It is important that we receive training to learn how to use those resources to advance our research. Now, we can identify patterns and improve our understanding of mechanisms across systems in a way that previously was unavailable. For me, that's a lot of revisiting existing ideas from ecologists and thinking about how we can make connections across ecosystems to make more general theories about how those ecosystems work and respond to climate and influence it. From that perspective, I think NEON is unique in that it provides paired observations across ecosystems that span a gradient of climates. Now that NEON is a presence in the ecology world, it's become an important resource for scientists like me who work across ecosystems.

From a societal perspective, we know that the risks of climate change are affecting people now and are going to continue to do so. We need to have a better understanding of how ecosystems respond to climate and also how they influence it. We know that government, communities, and individuals are going to have to spend a lot of money to mitigate the impacts of climate change. As a scientist working with ecosystems, part of my job is to provide people with the best information possible, and one of the things that is currently lacking in the research is putting together carbon cycle budgets across systems and thinking about the way that they exist in the environment. Making those connections, I think, is going to provide a lot of new information for stakeholders.

What is the most fun part about being an ecologist and what is the most challenging?

The most fun part is that ecosystems are very complex; I love puzzles, so I enjoy having the opportunity to disentangle these complexities. The most challenging part is that ecosystems are so interesting; so therefore I have many, many questions about them. Having to pick where to focus my efforts despite having tons of other questions in the back of my mind is the most challenging.

What challenges have you faced in the field of STEM, what advice would you give?

I have seen challenges as an ecologist that began in my teenage years, specifically in my high school STEM classes. I was held to a different standard than some of the men in my classes. I think this became evident then because my school had a system where you could pick more advanced classes that needed you to meet certain requirements, which I met. Yet I was refused from an advanced class by a teacher; held to a higher standard. Those things can be demoralizing, but I think it also happens in more subtle contexts. It could be moving up into the next stage in your career and suddenly noticing fewer women around you. It can be ill-intentioned comments from professors or people who have power over you, such as a supervisor for your Ph.D. Luckily, I have had wonderful, supportive mentors. And thankfully, I have seen that the landscape is changing, and those demoralizing things are becoming less acceptable to everybody in academia.

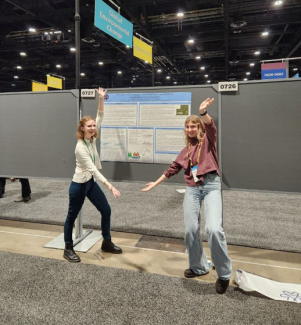

Talbot (right) and her undergraduate research assistant, Eva Deegan (left) in front of Eva’s first research poster at the 2022 American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting (now Annual Meeting) in Chicago, IL. Eva Deegan is now a Ph.D. student at Northern Arizona University. Photo credit: Alexis Renchon.

I think my biggest piece of advice would be to not internalize what people around us say or do, because at the end of the day, we can’t control it. For me, having supervisors who were aware that women have a different experience in this field and being able to validate my feelings allowed for a powerful experience. Surrounding yourself with peers who have similar experiences to you is also helpful. It can be difficult, especially if you're in a field where you're not surrounded by a lot of women. You can't control the people around you, so trying to find support in any way you can, whether it's from your supervisors, friends, or peers is the way to go.

Are you confident that the scientific community will be able to solve the world's biggest ecological issues? What barriers do you think need to be removed in order to do so?

The biggest change is that we need to get better at collaborating and inviting new voices to the table. Having a diversity of perspectives across all fields is important, and I think within projects and groups at every level, having people who have different experiences, whether it’s related to education, nationality, gender, etc. is important. I like seeing how different people arrive at different solutions, and I think that if we're collaborating and diversifying the people we're working with every day, it’s the right path forward.

What do you hope to do in your field in the future? Are there any specific areas of research in which you want to do more work or see more investment?

In general, I'd like to see more cross-ecosystem work in the future. I think that could come in the form of meta-analysis or synthesis work and collaborations between people who work in different systems such as terrestrial ecology, aquatic ecology, coastal/estuarine, and more. It’s necessary to consider that all of these systems are complex in their own right, but I think there is also a lot in common between them. I would really love for people to embrace that because there is a lot to learn from what we've already done. For example, processes like photosynthesis and respiration occur across systems. Are there frameworks that were developed in lake ecosystems that could be applied to forest ecosystems? Are ecosystems near each other experiencing change in response to the same shifting temperature? This is an area of ecology I hope to explore more.

Talbot driving the field work boat on Bay Lake at University of Notre Dame Environmental Research Center. Photo credit: Randi Notte.