AGU-TEX Project Update: Advocating for Environmental Justice in South Tucson

November 20, 2024

PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a growing public health and environmental concern in communities around the globe. A community project, facilitated through the American Geophysical Union Thriving Earth Exchange (AGU-TEX) program and coordinated by Katie Matthiesen, is spreading awareness of PFAS dangers among residents in South Tucson, AZ.

While at the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON), Matthiesen worked with Linda Robles, the founder of the Tucson Environmental Justice Task Force, and Amelia Staniszewski, a graduate student in epidemiology at the University of Colorado Anschutz, to create educational materials highlighting the specific risks for South Tucson residents.

This work intersects not only with NEON’s commitment to community education, but also with the PFAS work conducted by Battelle, which manages NEON on behalf of the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF). Battelle has been operating at the cutting edge of PFAS research for more than two decades and is pioneering solutions for PFAS analysis, environmental assessment, destruction, and remediation.

PFAS Exposure: The Intersection of Ecology and Public Health

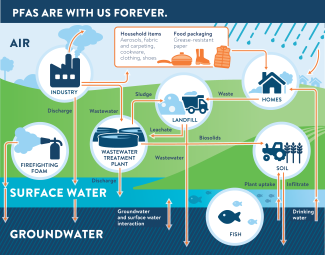

PFAS are a group of man-made chemicals used in various industrial and consumer products due to their water- and grease-resistant properties. They have been used in items like non-stick cookware, waterproof clothing, firefighting foam, and food packaging. PFAS are often referred to as "forever chemicals" because they do not break down easily in the environment and can persist for a long time in water, soil, and air, and accumulate in plant and animal tissues, with significant impacts on wildlife and ecosystems. PFAS chemicals have been linked to various adverse health risks, including hormonal disruptions, developmental and reproductive effects, liver damage, thyroid disease, and several forms of cancer. Recently, they have been heavily in the news due to new Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) limits on PFAS in drinking water, growing scrutiny by individual states (e.g., California, North Carolina, New Jersey, and New Mexico), and a rising tide of PFAS-related lawsuits.

"PFAS are forever chemicals. Old landfills, industrial sites, firefighting foam, and wastewater treatment discharge are just some of the ways PFAS can contaminate the environment. It then ends up in our groundwater and surface water resources and soils which impacts the water we drink, and the fish and grown food that we eat." - Credit: University of Nebraska Lincoln.

South Tucson residents in Pima County, Arizona have been heavily impacted by PFAS contamination from nearby airport and military installations. The predominantly Hispanic and low-income community has been disproportionately affected by cancers (including prostate, colorectal, breast, and lung cancers) and other health problems that have been linked to PFAS exposure. "PFAS exposure tends to be correlated with geographic proximity to things like airports, naval bases, and firefighting stations,” Staniszewski explains. “Historically, literature reviews tell us that BIPOC communities tend to be in near proximity to these locations. So, what we were really looking into was observed health inequities in South Tucson, knowing that this is a predominantly Latin American indigenous community."

As a graduate student in epidemiology, Staniszewski's role in the AGU-TEX project was to dig into the environmental and public health information for South Tucson. She collected and analyzed available data from the EPA, the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (AZDEQ), Arizona State University (ASU), local hospitals, and other data sources to compile specific community information about exposures and health outcomes. She then worked with Robles and Matthiesen to create educational materials in English and Spanish to bring awareness to the community.

For Linda Robles, environmental justice is highly personal. She started the Tucson Environmental Justice Task Force after losing her daughter to kidney failure and a rare cancer related to lupus. Her younger daughter and son were later diagnosed with rare diseases, and her niece died of a rare childhood brain cancer. She also witnessed many other people in her community getting sick with similar illnesses, which she believes is related to high exposure to PFAS chemicals, trichloroethylene (TCE), and other toxins in the drinking water in South Tucson. State investigators later confirmed extremely high concentrations (70,000 ppm) of PFAS in drinking water in south and central Tucson. Robles is now one of the country's leading advocates for clean air and water in Latino communities.

Robles, Staniszewski, and Matthiesen worked together to create community-specific education materials for South Tucson residents to spread awareness of PFAS risks and effects. The brochures share information about PFAS chemicals and how people in the community can protect themselves, for example, by using reverse osmosis water filters to remove PFAS from drinking water.

Staniszewski says, "The goal was to empower and educate people to make informed decisions on their own and prevent adverse outcomes from PFAS exposure. We wanted to make the information very accessible for people and help them understand the contamination levels of water supplies in different parts of the city and how certain health outcomes might be related to PFAS exposure. We want people to be able to advocate for themselves, whether that is with a doctor or in choosing filtration technologies to protect their families."

Brochure created for South Tucson residents to spread awareness of PFAS risks and effects and show how people in the community can protect themselves.

Download the South Tucson PFAS Flyer

Descargue el folleto sobre PFAS del South Tucson

As an ecologist, Matthiesen added valuable expertise to help support the educational mission and provide technical information about PFAS risks and remediation options. In September of 2023, she and Robles participated in an EPA task force on PFAS in Washington DC, where they met with dozens of representatives, senators, EPA officials, and policy makers to advocate for PFAS limits in drinking water limits and a broader and more standardized definition of PFAS chemicals. The EPA announced the new limits for PFAS in drinking water in April 2024.

Staniszewski says ecology and epidemiology are highly interconnected. Environmental factors, including contaminants, can have a large impact on public health outcomes. She says, "NEON is great for epidemiologists because it offers that multifaceted approach that epidemiologists need. Epidemiology goes beyond just hospital settings. A project like this showcases the need for collaboration between epidemiology and other disciplines, especially ecology and environmental science, because it's all interrelated."

For Roble’s part, she says, “Working with Katie and Amelia was wonderful. I hope that we can continue to grow in capacity building.”

Reflecting on the TEX Experience

Katie Matthiesen served as a Field Ecologist for Domain 14 (Desert Southwest) from 2016-2024. During her time at NEON, she coordinated observational sampling for terrestrial fauna including small mammals, ground beetles, mosquitos, and ticks. She has always been very passionate about community outreach.

Can you describe your overall experience with the program? Was it what you expected?

I am glad I participated; the overall experience has been positive. The general workflow was not quite as expected originally, but we adapted and worked towards a goal and kept driving engagement with the community in South Tucson.

Were the goals of the community able to be met through the project? If so, how? If not, why not?

I encouraged my community lead to identify a top goal of disseminating relevant PFAS educational materials, and I think we met that top goal quite well. If we had tried to continue with all the community's goals, it would have taken more time and financial means. I think I was able to accomplish the project goal by getting lucky in finding an expert partner quite quickly—someone who was motivated and excited about the project. I think as a TEX Fellow, taking charge and taking a driver's seat approach helped us to succeed in this aspect.

Do you feel the project was successful? What were your successes?

I definitely do. Beyond the educational pamphlet about PFAS in South Tucson we created, I know I have built a relationship with my community lead and the expert I brought in. I hope they continue to work together. I made a great working relationship with the community lead as well, and I think she made new beneficial relationships.

I also got to do a DC fly-in to support my community lead, meet her inner circle, and learn more about the project. I had never before had meetings with senators and White House officials. It was definitely a professional development moment.

What was the most important contribution you made to the project team as a Fellow?

Keeping that momentum going to accomplish our goal, to build the enthusiasm for spreading awareness and education, and to make sure everyone stayed engaged.